SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket lifted off from Cape Canaveral at 1:22 a.m. EDT (0522 GMT) Thursday with the Hotbird 13G communications satellite. Credit: Stephen Clark / Spaceflight Now

SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket lifted off from Cape Canaveral at 1:22 a.m. EDT (0522 GMT) Thursday with the Hotbird 13G communications satellite. Credit: Stephen Clark / Spaceflight Now

SpaceX launched the second in a series of three Falcon 9 rocket missions early Thursday for the European satellite operator Eutelsat, delivering to orbit a television broadcasting craft that also hosts an EU-funded payload to provide precise navigation data to airplanes.

After a two-hour delay, the Falcon 9 rocket ignited its nine Merlin main engines and climbed away from pad 40 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station at 1:22 a.m. EDT (0522 GMT) Thursday to begin a 36-minute mission to deploy Eutelsat’s Hotbird 13G communications satellite into an elongated transfer orbit stretching as far as 35,700 miles (57,500 kilometers) from Earth.

Hotbird 13G separated from the Falcon 9 rocket as it soared over Africa. The new communications satellite completed initial post-launch activation steps, according to Eutelsat, and will use on-board plasma thrusters to maneuver to its operational orbit hovering more than 22,000 miles (nearly 36,000 kilometers) over the equator.

The Falcon 9 mission early Thursday occurred less than two days after SpaceX launched a Falcon Heavy rocket, the world’s most powerful active launcher, from a launch pad at Kennedy Space Center a few miles north of Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. The Falcon Heavy deployed two main satellite payloads into geosynchronous orbit for the U.S. Space Force.

It was the fourth flight of SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket, and the first Falcon Heavy launch in more than three years. With that mission in the books, SpaceX’s attention turned back to the company’s workhorse rocket, the Falcon 9, with a commercial satellite delivery flight for Eutelsat.

The 229-foot-tall (70-meter) Falcon 9 rocket headed east from Cape Canaveral with its nine engines generating 1.7 million pounds of thrust. After soaring through a broken deck of clouds, the Falcon 9 shed its first stage booster about two-and-a-half minutes into the flight, while a second stage engine took over to power Hotbird 13G into orbit.

Liftoff of SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket with Eutelsat’s Hotbird 13G satellite, launching a new TV broadcasting platform to provide service in Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. https://t.co/8fD75oz9oD pic.twitter.com/uOKGt0aXuP

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) November 3, 2022

Two burns by the upper stage engine propelled the Hotbird 13G spacecraft into an on-target “supersynchronous” transfer orbit, with an apogee, or high point, far above the satellite’s final operating altitude. The Falcon 9 released Hotbird 13G into an orbit with a perigee, or low point, around 255 miles (410 kilometers), and an inclination of 27.7 degrees to the equator, according to U.S. military tracking data.

Hotbird 13G, which weighed about 10,000 pounds (4.5 metric tons) at launch, separated from the Falcon 9’s upper stage around 36 minutes into the mission. A live camera view from the rocket showed the spacecraft flying free of the upper stage. The satellite will maneuver from its current elliptical orbit to a circular geosynchronous orbit over the next few months. Eutelsat expects Hotbird 13G to be ready for commercial television broadcast services around mid-2023.

The first stage of SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket extended hypersonic grid fins and reignited three of its engines for a braking burn during re-entry back into the atmosphere. The reusable booster — designated B1067 in SpaceX’s fleet — lit its center engine for a final landing burn to settle onto the deck of a SpaceX drone ship in the Atlantic Ocean. The landing completed the booster’s seventh trip to space, and the drone ship will bring the rocket back to Cape Canaveral for refurbishment and preparations for a future flight.

The launch Thursday morning was the 51st mission of the year for SpaceX, and the 48th space launch attempt from Florida’s Space Coast so far in 2022. Both are records.

Hotbird 13G’s deployment follows the launch of a twin satellite named Hotbird 13F, which rode a Falcon 9 rocket into orbit from Cape Canaveral on Oct. 15.

After launching from Cape Canaveral with Eutelsat’s Hotbird 13F communications satellite, the Falcon 9’s first stage booster has landed on a drone ship in the Atlantic Ocean.

This booster — designated B1067 — has now launched and landed seven times.

https://t.co/8fD75oz9oD pic.twitter.com/rZwvOII9vc— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) November 3, 2022

Hotbird 13G is the second satellite built on the new Eurostar Neo spacecraft platform designed by Airbus Defense and Space, with funding support from the European Space Agency. The Eurostar Neo satellite design can accommodate additional payload capacity, and introduces more efficient power and thermal control systems than the previous generation of Eurostar E3000 Airbus-built satellites.

The Hotbird 13F satellite launched last month was the first to use the new Eurostar Neo spacecraft design.

“It’s a huge new product, payload centric, more competitive than anything we have ever done,” said François Gaullier, head of telecommunications satellites at Airbus, in a press conference last month.

ESA provided about 130 million euros, or $126 million at current exchange rates, to help pay for development of the new satellite platform. Airbus funded the rest of the development cost with its own money under the umbrella of a public-private partnership.

Eutelsat was the first customer to sign up for the new spacecraft design, inking a contract in 2018 for Airbus to build the Hotbird 13F and 13G on the Eurostar Neo platform.

So far, Airbus has sold eight satellites based on the new Eurostar Neo platform, including Hotbird 13F and 13G. Other customers for the Eurostar Neo satellite design include the UK Ministry of Defense, which signed a contract with Airbus to build a secure military communications satellite on the new spacecraft platform.

Hotbird 13G separation.

Eutelsat’s newest TV broadcasting satellite, built by Airbus, has deployed from SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket. The 4.5-metric ton satellite will use plasma propulsion to maneuver into geosynchronous orbit in the next few months.https://t.co/8fD75oz9oD pic.twitter.com/O9H5YFWPwU

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) November 3, 2022

Airbus delivered the Hotbird 13G spacecraft from its factory in Toulouse, France, to Kennedy Space Center on Oct. 15, hours after the launch of its sister ship Hotbird 13F. One of Airbus’s large Beluga cargo airplanes, typically used to haul Airbus airplane parts between manufacturing sites in Europe, ferried the Hotbird 13G satellite from France to the United States.

Hotbird 13G, like Hotbird 13F, will orbit in lock-step with Earth’s rotation at 13 degrees east longitude.

Thanks to improvements in satellite communications technology, Eutelsat will only need two new Hotbird satellites to replace the three aging Hotbird spacecraft operating at 13 degrees east.

Pascal Homsy, Eutelsat’s chief technical officer, said the Hotbird fleet at 13 degrees east form the highest capacity satellite broadcasting system covering the Europe, Middle East, and North Africa regions, delivering 1,000 TV channels to more than 160 million homes. Hotbird 13F and 13G will broadcast signals in Ku-band frequencies.

“We have something like over 600 pay TV channels, 300 free to air channels, 450 high definition TV, and 14 ultra high definition channels broadcast from this flagship 13 degrees east position,” Homsy said last month before the launch of Hotbird 13F. “We are able also to provide 500 radio stations and multimedia services.”

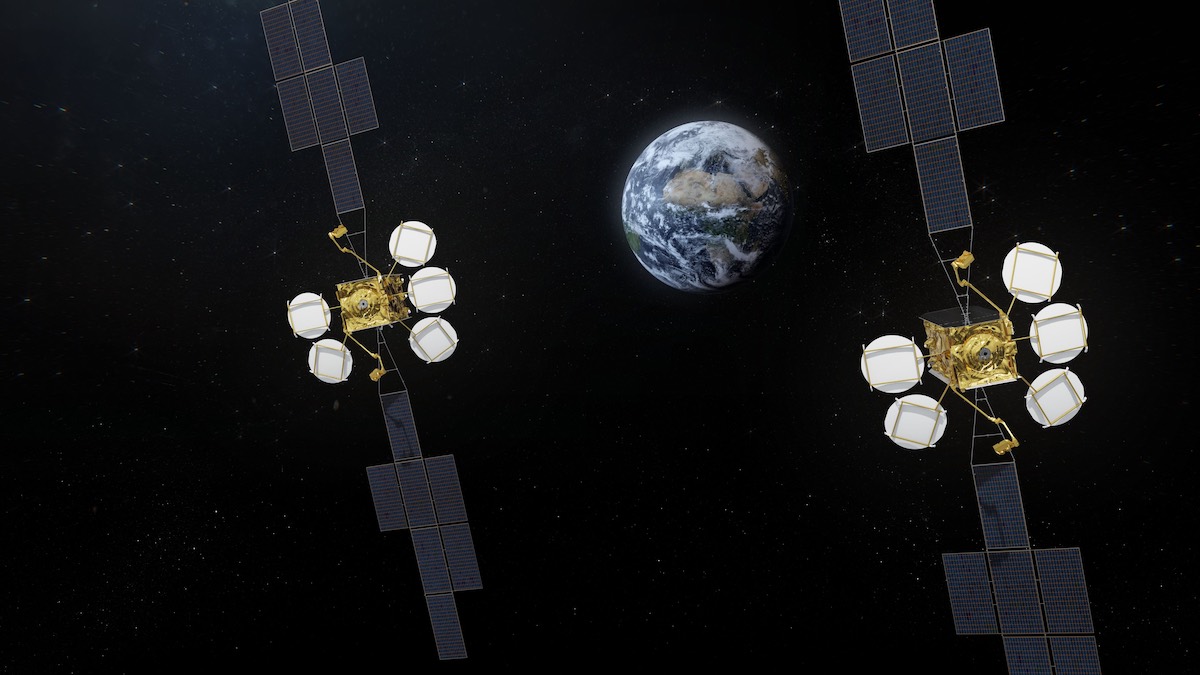

Artist’s concept of the Hotbird 13F and 13G satellites with their solar panels and antennas unfurled in orbit. Credit: Airbus

Artist’s concept of the Hotbird 13F and 13G satellites with their solar panels and antennas unfurled in orbit. Credit: Airbus

Hotbird 13G also hosts a geosynchronous orbit node for the European Geostationary Navigation Overlay System, or EGNOS, to beam GPS and Galileo navigation augmentation signals to improve position accuracy and reliability. The EGNOS signals provide additional navigation data for use by pilots during critical flight stages, such as final approach and landing.

The European Union Agency for the Space Program awarded Eutelsat a 15-year deal in 2021 to accommodate the EGNOS payload on Hotbird 13G. The contract was valued at 100 million euros ($97 million). The addition of the EGNOS payload is the main difference between Hotbird 13G and its predecessor Hotbird 13F.

Aside from aviation, EGNOS signals are used in precision farming, surveying and mapping, rail transport, and by the maritime sector to help ships navigate through narrow channels.

The launch of Hotbird 13G is the second in a series of three Falcon 9 flights for Eutelsat. The Eutelsat 10B communications satellite, designed to provide in-flight internet connectivity to airline passengers, was delivered from Europe to Cape Canaveral by boat last week for a launch on a Falcon 9 rocket later this month.

SpaceX’s next launch is scheduled from Cape Canaveral on Nov. 8, when a Falcon 9 rocket will deploy two Intelsat television broadcasting satellites. The Falcon 9 booster on the next launch will not be recovered, allowing the rocket to devote all of its propellant to powering Intelsat’s Galaxy 31 and 32 satellites into orbit.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.